How I learned Chinese

Note: I wrote this article in May 2020. I am re-upping it now, in February 2021, because I am (finally) getting ready to put out a Chinese translation.

I have been learning Chinese for just over three years. Over the past month, more and more people have been asking how I learned Chinese. Today I’ll explain my process. But before I start explaining the process, there are a few bits of “common knowledge” which I consider unhelpful and hope to dispel:

You have to start learning a language as a teenager in order to be able to attain native speaker level. I started studying Chinese at age 29 and speak well enough to live in China without needing English. Also, who cares whether or not you get to “native” level? The purpose of learning a language is to communicate and enjoy another culture, not to show off.

Younger brains learn language faster. From 2017 until now, I have learned more Chinese than, say, a child learns between 7–10 years old. I can write emails about complicated subjects, I can write essays, I can discuss life experiences and life philosophies with friends, I can write jokes on Twitter, etc. These are things a 10 year old can’t do well.

You can’t learn a language unless you have a talent for languages. The dumbest American you know still speaks English just fine.

You can learn faster with XYZ method! There are no shortcuts. Any app/program/product which says you can learn a language by practicing for 30 minutes per day is pure bullshit.

Chinese has a saying which serves as a solid guide for learning a new language: “Read more, write more, speak more, listen more.” I don’t believe that learning a language requires the most efficient learning system or best methodology. Of course these are helpful, but there is simply no substitute for time. The challenge is that the process of learning a language can be both incredibly dull and discouraging. It is easy to give up, either out of boredom or desperation, before putting in enough time to become self-sufficient.

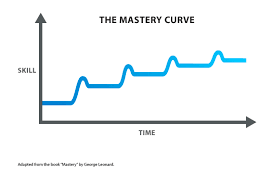

To give an example, there is almost nothing more boring than writing Chinese characters (汉字/hànzì) over and over until they solidify in your memory. I estimate that in 2017, I wrote approximately 1 million characters (~5000 characters 200 times each). To make matters worse, there is not a linear progression of Time vs Skill. After weeks of hammering away, I would notice a perceptible jump in my ability, followed by another 3–4 weeks of plateau. Each time I hit a plateau (see The Mastery Curve below), the “asshole in my head” would tell me: “You’re almost 30 you idiot, it doesn’t matter how much you study, you’ll never learn Chinese. You gave up a full time job for this. How stupid can you be?” The only option is to keep going.

The key is to figure out ways to make “studying” palatable enough that you can do it for many hours per day, months on end, without throwing in the towel. I put “studying” in quotation marks because study can (and must) include a wide variety of activities other than classwork and textbooks. I’ll discuss more below.

Before beginning classes in Beijing in 2017, I spent a month learning basic vocabulary and pronunciation using the app Chinese Skill. Next, I started five months of classes at a university in Beijing. During these months, between classes and self-study at home, my daily study time during was 12–15 hours per day. After finishing the semester, I became self-sufficient, an incredibly important milestone in the course of learning a language. In other words, I could speak and understand enough Chinese to hold meaningful conversations with people. Once you have reached this point, classes become less important, as you can continue learning simply by living and interacting in a Chinese language environment.

Note: in order to minimize the time needed to reach self-sufficiency, I did not make a single foreign (English-speaking) friend in my first six months. This was to make sure I was immersed in Chinese all day every day. Thus in addition to the boredom and the despair often felt during each plateau, learning Chinese at speed requires you to conquer loneliness as well.

In the following six months I did self-study for 3–5 hours a day while working. For the following two years, I worked with Chinese companies and spoke Chinese daily during work. During that time I was also taking one-on-one classes two times per week, two hours per class. Classes were a good way to supplement the informal study/learning that I was doing in the workplace. In the past six months, I have not been studying formally but still speak and write Chinese every day. That brings us to the present day.

Below, I will talk more about my methods to improve the four skills mentioned in the Chinese saying above: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. I will also talk about the importance of hànzì (Chinese characters) and vocabulary .

汉字/hànzì: I’ve met some foreigners in China who speak decent Chinese but are not skilled at reading Chinese characters. Up to a certain point, you can learn to speak and understand Chinese without memorizing characters. However, without a command of characters it’s impossible to understand Chinese in the same way a native speaker does. If you find yourself unsure of what to study at a given moment, learning characters is always a good way to spend your time. For me, learning characters consisted of writing a character 20–30 times while saying its pronunciation out loud and repeating its meaning in my head. Boring, but necessary.

Vocabulary: To a degree, the notion of vocabulary is contained within hànzì. Sometimes a single hànzì can be used as a vocabulary word. Other times, words consist of multiple characters (usually 2 to 4). In any case, I prioritize rote learning of vocabulary over grammar. This is because vocabulary is the most basic building block of a language. If you have heard a word before and you hear it in a sentence that contains unfamiliar grammar, you might be able to “reverse engineer” the grammar being used in the sentence. On the other hand, no matter how much grammar you know, if you have no idea what a word means it becomes difficult to follow along. This is especially true with Chinese, where the vocabulary words bear absolutely zero resemblance to Romance languages. For this reason, in my first year of studying, whenever I was commuting somewhere, whether by plane, train, or automobile, I was reviewing flashcards. The Pleco dictionary app is particularly good for this. Any time I ran into a word in my flashcard deck that I didn’t know, I would save it for later and then write it 15 to 20 times so that I retained it.

Listening: Being able to understand a language is more important than being able to speak it. Only when you’re able to keep up with a conversation can you contribute to it in meaningful ways. One of the challenges with listening comprehension in Chinese is the variety of accents. After leaving Beijing I was confident in my listening abilities. But when I got to Shenzhen, where the most common accents are Guangxi, Hunan, or Guangdong, I found myself unable to understand much for the first few weeks. It took some getting used to. Here are some of the methods I recommend:

Podcasts: My favorite podcast for learning Chinese is Slow Chinese. They cover Chinese culture and history in episodes which range from 3 to 10 minutes. They speak slowly and provide a transcript with each episode. Listening to the episode while reading along with the script is an effective way to practice listening and reading at the same time. Once your reading is good enough, you can mouth the words as the podcast is playing. Slow Chinese is too difficult for beginners, but once you have some basic vocabulary under your belt you can start listening to it. Even if you don’t understand the majority of what is being said, it is helpful to accustom your ears to the language. After a year of studying, I started listening to podcasts meant for Chinese people (eg, not for Chinese learners). My favorites are: 声东击西, 文化土豆, 硅谷早知道, and 海马星球. At this point I can understand 99% of what’s being said. However, in my second year of learning Chinese, I would listen to every podcast twice. The first time I would pause and create a flash card every time I heard a word I didn’t understand. I would study the flash cards and then listen to the entire episode again.

TV and movies: For learning purposes, TV series are better than movies simply because they are longer and therefore allow you more time to understand the context and storyline. The more you understand the context of what is happening (and what is likely to happen next), the more your brain can “fill in the blanks” when you run into vocabulary you don’t understand. iQIYI and Youku both have plenty of content to choose from (though you may have to get a VPN to convince the website you’re browsing from China). I recommend picking shows or movies based on category — pick a category that you really like. That way, even if you can’t understand everything that’s being said, you can still enjoy watching. I enjoy action movies and cop dramas. Some of my favorite series were 破冰行动, 无证之罪, and 白夜追凶. Note: I never used English subtitles, always opting for Chinese subtitles instead. When English subtitles are on, thats’ all your eyes will see.

Speaking: Speaking is a good way to synthesize what you’ve learned through other forms of study — eg, trying out new grammar you learned in class or vocabulary that you learned from podcasts. While I was learning Chinese, I was living with my girlfriend who speaks Chinese. She was supportive of my goal to learn and spoke Chinese with me in the house. She traveled often for work. When she was away, although I am a little embarrassed to admit this, I would often practice speaking by talking to myself. I found this to be useful for training my tongue and improving muscle memory.

Although living with someone who speaks the language you want to study is convenient, it’s not at all necessary. When I studied abroad in Japan in college, I found two bars which I really enjoyed. They were small, fairly quiet, and catered mostly to Japanese people in their late 30’s or early 40’s who were already settled in their careers. This is important because younger people tend to view learning English as a way to boost their career prospects and would thus want to speak English with me. The late 30’s / early 40’s crowd seemed to view speaking English as tiresome, so they spoke Japanese with me. During my 5 months in Japan, I went to one of these two bars almost every night and stayed for 3–4 hours each time.

When we moved to Shenzhen in 2018, we had more of a social life than we did in Beijing. I improved my speaking there simply by hanging out with friends a couple of times per week. My speaking improved further when I started working in a Chinese language environment.

Reading: In my opinion, reading is the best form of studying. You don’t have to read academic articles or textbooks in order to learn. Reading novels or comics is just as good, if not better. Similar to a TV series, the storyline in a novel develops over hundreds of pages, allowing your brain to get into the context of what’s happening. You’ll see similar vocabulary used repeatedly throughout the book, increasing the chance that these words will stick with you after you’ve finished. The challenge is finding material that’s at your reading level because nothing is more frustrating than having to pick up a dictionary every 30 seconds to look up new words. I use a couple of strategies to deal with this:

Read things that you have already read in another language. When I was learning Japanese, the first full books I read were Haruki Murakami’s Dance Dance Dance and The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. I had read both of these in English prior to picking up the Japanese versions. Murakami’s books inevitably use tons of vocabulary I have never seen before. However, because I had already read the books in English, I already knew the storyline. That way, when I would encounter words I didn’t know, it didn’t disrupt my understanding of the story as a whole. It’s like walking into a room you’ve been in before. When learning Chinese, I read comics (死亡笔记 and 进击的巨人) that I had already read in Japanese years earlier.

Read books for which you’ve already seen the movie or TV series. Like the strategy above, this enables you to understand the storyline even if you encounter words you don’t know. Reading is fun if you can do it without a dictionary. If you have to look up multiple words on every page, your brain will never actually get into the story and you’ll quickly become bored. I liked the TV series 无证之罪 and the movie 嫌疑人X的献身 so I read the books after watching.

Read comics. Comics tend to be geared towards a younger audience than novels. They use simpler language and also include pictures. The pictures help you understand the storyline even if you encounter unknown words. Again, the goal is to avoid using a dictionary as much as possible.

Read books twice. In my 2nd and 3rd years of studying Chinese, I would read every book twice. The first time, I would create flashcards for every word I didn’t know. I would memorize every word and then read the book again. The goal for the second read was to get through the entire book without using a dictionary. Doing this requires discipline because your first time reading the book will be slow and frequently punctuated with visits to the dictionary; however, the second read is extremely rewarding because not having to look anything up makes you feel like a native speaker.

Writing: Writing is the best way to master new vocabulary and grammar. It is more deliberate than speaking and does not have the same time pressure that a conversation does. Reading more is the best way to learn to write. Aside from writing short essays for class, I started using WeChat (China’s omnipresent messaging app) to chat with Chinese friends early on. Communicating through messaging apps is a great way to improve both your reading and your writing. If you don’t have Chinese friends to communicate with, you can seek out interest-based WeChat groups to get exposure to a steady stream of conversational written Chinese. You can start chiming in when you feel comfortable doing so.

Starting in 2020, I began writing short essays in Chinese as well. Although I have not published them (on Chinese social media as originally intended), the act of writing and polishing was helpful to further improve my writing and speaking skills.

This piece is a thorough accounting of what I did to learn Chinese between early 2017 and today. I understand that not everyone can take six months off work like I did to study full time. Nonetheless I hope that my experience gives you confidence that you can learn a language regardless of your age or (perceived) language ability. If you are able to take half a year to dedicate to studying, I am confident you can learn a new language as well.

Learning Chinese can feel overwhelming at first with all the characters and tones to master. You might find CoachersOrg helpful since they offer personalized lessons that adapt to your pace and style. With steady practice like that, you could build real confidence in reading, writing, and speaking over time.

说得好,我也是在成年以后才开始学英语。那时既无老师又没有学习材料。我的政策就是拒绝看任何中文资料。两年不到我就能看狄更斯和英译版托尔斯泰。